THE TEN COMMANDMENTS

Open configuration options

Commandments??? The Hebrew word used (Aseret HaDibrot; Ten the Sayings)clearly means “sayings” or “things.” The Hebrew word is still used today with the same meaning. The Catholics changed the correct translation to the word “commandments” about 400 years ago.

When you look at the first “commandment” is says; “I am yhvh your God, who brought you out from the land of Egypt, and from the house of serfs.” There is no commandment it that sentence. So the Catholics didn’t want 9 commandments, so they took the second commandment and divided it into two parts and made the first part the first commandment.

The first part is; You are not to have any other gods before my presence. The second part is: You are not to make yourself a carved image or any other figure that is in the heavens above, earth below, or the waters beneath the earth.

Then the Catholics said; “We can’t have that second part as a commandment, the people love the super-hero statutes of our captivating fable. And saying Jesus is god brings in a huge amount of people. Now we have 9 commandments again. Lets make the last commandment two parts, one being commandment 9 and the other commandment 10!”

The Protestant Christians who broke away from the Catholics wanted emphasis on the fact that they didn’t like the super-hero statutes of the Catholics, so they made sure to make the second commandment not to worship graven images.

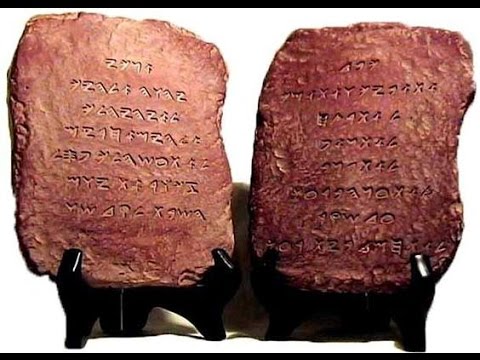

LAW/CODE TABLETS

The lawgiver archetype usually includes a law code or codes, comprising commandments of one sort or another. To reiterate, the Ten Commandments evidently represent a modified version of various ancient writings, such as in Egyptian, Babylonian and other texts. In addition to the 10 Commandments are the numerous laws in the books of Leviticus, Deuteronomy and elsewhere, such as at Exodus 20:22–23:23. In this regard, this biblical “Book of the Covenant” reflects the “Canaanite variation” of the various civil codes of the second millennium BCE, such as the laws of the Babylonians, Hittites and Assyrians.

MOSES

20 The Lord descended to the top of Mount Sinai and called Moses to the top of the mountain. So Moses went up Exodus 10:20

The Lord there communed with him, and

18 When the Lord finished speaking to Moses on Mount Sinai, he gave him the two tablets of the covenant law, the tablets of stone inscribed by the finger of God. Exodus 31:18

19 When Moses approached the camp and saw the calf and the dancing, his anger burned and he threw the tablets out of his hands, breaking them to pieces at the foot of the mountain. Exodus 32:19

Moses again saw the Lord on the Mount, however, and received two more tables of stone;

34 The Lord said to Moses, “Chisel out two stone tablets like the first ones, and I will write on them the words that were on the first tablets, which you broke. 34:1

29 When Moses came down from Mount Sinai with the two tablets of the covenant law in his hands, he was not aware that his face was radiant because he had spoken with the Lord. 30 When Aaron and all the Israelites saw Moses, his face was radiant, and they were afraid to come near him. Exodus 34:29-30

BACCHUS

Bacchus, as well as Moses was called the “Law-giver,” and that it was said of Bacchus, as well as of Moses, that his laws were written on two tables of stone. However Bacchus did not assend a mountain. That mountain part of the Moses/Tablets story was borrowed from the Persian legend of Zoroaster.

Bacchus was represented horned, and so was Moses.

ZOROASTER

The legend of the master Zoroaster, relate that one day, as he prayed on a high mountain, in the midst of thunders and lightnings (“fire from heaven”), the Lord himself appeared before him, and delivered unto him the “Book of the Law.” While the King of Persia and the people were assembled together, Zoroaster came down from the mountain unharmed, bringing with him the “Book of the Law,” which had been revealed to him by Ormuzd (God). They call this book the Zend-Avesta, which signifies the Living Word.

CRETANS

Minos, their law-giver, ascended a mountain (Mount Dicta) and there received from the Supreme Lord (Zeus) the sacred laws which he brought down the mountain with him.

THOTH FINGER

The Egyptian belief, is that Thoth, the Deity itself, that speaks and reveals to his elect among men the will of God and the arcana of divine things. Portions of them are expressly stated to have been written by the very finger of Thoth himself; to have been the work and composition of the great god.

BUDDHA

Buddha, the founder of Buddhism, had TEN commandments. 1. Not to kill. 2. Not to steal. 3. To be chaste. 4 Not to bear false witness. 5. Not to lie. 6. Not to swear. 7. To avoid impure words. 8. To be disinterested. 9. Not to avenge one’s-self. 10. Not to be superstitious.

EBLA AND BAAL-BERITH

In the Ebla texts from the third millennium BCE can be found numerous Semitic religious and social practices that predate similar Hebrew doctrines, rituals and traditions by many centuries. These analogous practices include a complex legal code and scapegoat rituals, preceding not only the Hebrew but also the Canaanite/ Ugaritic cultural equivalents. There is little reason to suppose that the Israelite law truly was handed down supernaturally by Yahweh to a historical Moses, rather than representing a continuation of this very old code.

Walker relates that the “stone tablets of law supposedly given to Moses were copied from the Canaanite god Baal-Berith [Jdg 8:33], ‘God of the Covenant.’” She then adds that the Canaanite Ten Commandments were “similar to the commandments of the Buddhist Decalogue” and that, in the ancient world, “laws generally came from a deity on a mountaintop,” such as in the story the Persian god Ahura Mazda giving the tablets of the law to the prophet Zoroaster or others discussed here, including Gilgamesh, Hammurabi and Minos.

EGYPTIAN BOOK OF THE DEAD

The basic sentiment of various biblical commandments can be found in the Egyptian Book of the Dead, particularly the 125th chapter or spell, which existed by at least the 19th century BCE. This spell contains much else beyond the 10 Commandments, however, resembling some of the numerous other commandments, ordinances and instructions of Exodus, Leviticus and Deuteronomy.

The Book of the Dead likewise depicts the “Hall of the Double Law or Truth where the divine lawgiver Osiris presided as Judge of the Dead.” It is before Osiris in this hall that the deceased must appear to state the 42 affirmations and denials or “negative confessions” about behaviors during the life of the deceased.

Because these are “negative confessions,” instead of the commandment, “You shall not steal,” the deceased, hoping for eternal life in heaven, states, “I have not stolen.”

ENKI, ENLIL AND THE TABLETS OF ME

Another code “divinely handed down” can be found in Inanna’s Descent (2nd millennium BCE) in the story of the “seven divine laws,” which the goddess Inanna “fastened at the side,” while placing in her hand “all the divine laws,” as she descended into the underworld. In a similar vein are the decrees or mes initially collected by Enlil, eventually given to his brother and Inanna’s father, Enki, god of wisdom and magic.

Fig. 56. Enki, Sumerian god of wisdom and fresh water, c. 2200 BCE. Cylinder seal, British Museum

The lawgiver, “king of the gods” and “ruler of the universe,” Enlil was also called “mountain” (kurgal), and his temple was the “House of the Mountain.” He was likewise the “prophet” or mouthpiece for the heavenly Anu or An, centuries before Moses on Mt. Sinai with Yahweh. Like Yahweh, Enlil both created mankind and destroyed it with a flood. The “biblical” counterpart is therefore archetypical and mythical, not reflective of “history.”

TABLETS OF DESTINY

This Mesopotamian myth about civilizing foundational decrees and godly gifts is reiterated in the Enuma Elish, in the Babylonian tale of Tiamat and the “tablets of destiny” After a fierce battle between Tiamat and Marduk reenacted during the spring’s New Year festival, these powerful artifacts ended up in the hands of Marduk, conferring upon their holder(s) the “supreme authority as ruler of the universe.”

THE CODE OF HAMMURABI

Detailed legal pronouncements for numerous situations can be found also in the Code of Hammurabi, which dates to the 18th century BCE and in which four of the 10 biblical commandments appear repeatedly.

For example, the ninth of the Ten Commandments or Decalogue is, “You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor,” whereas in the Code of Hammurabi, we read: “1. If a man bring an accusation against a man, and charge him with a (capital) crime, but cannot prove it, he, the accuser, shall be put to death…. 3. If a man, in a case (pending judgment), bear false (threatening) witness, or do not establish the testimony that he has given, if that case be a case involving life, that man shall be put to death.”

As another example, the familiar eighth commandment, “You shall not steal,” is similar to Hammurabi’s sixth commandment: “If a man steal the property of a god (temple) or palace, that man shall be put to death; and he who receives from his hand the stolen (property) shall also be put to death.” The punishment for breaking the biblical commandments likewise is death.

ROMAN TABLES OF LAW

In addition, it was the “custom among the ancients to [engrave] their laws on tables of brass, and fix them in some conspicuous places, that they might be open to the view of all.” In this regard, in his History of Rome (3.34–37), Livy refers to the “Laws of the Ten Tables” that were “passed by the Assembly of Centuries,” a legislative body called “Comitia Centuriata.”835 These were created around 451–449 BCE by 10 men or a decemvirate, who initially made 10 tables and then added two more. These 12 contained the Roman law code, called “Law of the Twelve Tables” or Lex XII Tabularum,836 which formed the core of the Roman Constitution, inscribed on 12 tablets or either ivory or bronze and hung in the Forum.

PLATO’S LAWS

A number of commentators in antiquity—including Aristobulus of Paneas (2nd cent. BCE) and Church fathers Justin Martyr, Clement of Alexandria (Strom. 1.22), Origen (182–254 AD/CE) and Eusebius (263–339 AD/CE)— pointed out the correspondences between Moses and Plato, attempting to make the latter the plagiarist of the former, to suit biblical doctrine and precedence. However, chronology tells another story, and there are recent scholarly efforts to demonstrate that the Mosaic law in the Pentateuch draws from Plato.

Aristobulus of Paneas supposedly was a wandering Hellenistic Jewish philosopher who studied in Alexandria during the second century BCE. It has been surmised that he is the Aristobulus to whom the Jewish apocryphal text 2 Maccabees (c. 124 BCE) is addressed, which indicates he may have known about the Jewish Dionysus worship discussed therein.

Aristobulus purportedly referred to a flawed earlier Greek translation of the Pentateuch that was replaced by the Septuagint. Interestingly, his account appears to be devoid of any indication of the events in Genesis, leading some scholars to conclude that the book was not in this earlier edition. The existence of this purported earlier Greek text, however, has been questioned.

In a fragment of his writings preserved by Church historian Eusebius (Praep. ev. 13.12), Aristobulus “deduces from certain previous discussions (no longer extant) that both Plato and Pythagoras drew upon a translation of the Mosaic Law before the time of Demetrius of Phalerus (and this before the Septuagint…).”

However, the editors of The Jewish Encyclopedia assert that “further examination of the works attributed to Aristobulus confirms the suspicion as to their genuineness aroused by their eclectic character” and that the quotes attributed to him are “probably spurious,” drawing upon the later Philo, for example. In any event, these quotes, which may date from the second century of the common era instead, demonstrate once more that in ancient times Moses and Plato were being compared.

Philo too was fascinated by Platonic philosophy, and “at many points we have the impression that he considered Plato as the Attic Moses.” The fact that Philo spends so much time on Plato, his “philosophical master” whom he calls “the most holy Plato” (Prob.13), demonstrates that Jews had been interested in the Greek philosopher for some time.

In Preparation for the Gospel (11.10.14ff), Eusebius spends considerable time on this subject of Plato “stealing” Mosaic ideas; however, modern scholarship recognizing the late dating of much of the Pentateuch may prove the opposite.

Concerning St. Augustine’s Platonic esteem and need nevertheless to subordinate the Greek philosopher to the Bible, Dr. Paul Ciholas remarks:

Plato’s influence on Christianity is discussed mostly in Books VIII and X of The City of God. There Plato is considered as one of the greatest minds of antiquity, superior to many gods. The task of Augustine is to vindicate the greatness of Plato while proclaiming him inferior to prophets and apostles.

The debt of Christianity to the Platonic system is only reluctantly conceded by Augustine…

Parallels between biblical and platonic ideology were so obvious in antiquity that it was surmised, as by Ambrose of Milan, that Plato had traveled to Egypt and the Levant, meeting with the prophet Jeremiah (655–586 BCE), son of Hilkiah the priest, who purportedly “found” the Pentateuch.

This anachronistic notion has been rebutted, and there is little evidence that pre-Christian Greek philosophy was influenced by Jewish texts, rather than the other way around. The fact that the Jewish scriptures needed to be translated into Greek demonstrates how popular, esteemed and entrenched was the Hellenization of the Mediterranean of the time.

Rather than assuming Plato had a copy of a text that does not appear in the historical record until centuries later—a text sacred to one of the most secretive sects, who thought it blasphemy for outsiders to read—it would seem that both Greeks and Jews had access to far older legal codes, as discussed here.

HECATAEUS OF ABDERA

The Mosaic law is not original and was not given to the Hebrew lawgiver by Yahweh via a miraculous event on Mt. Sinai. Regarding the Greek historian Hecataeus of Abdera, who was known in antiquity to have drawn up a foundational story for Moses and the Israelites, Gmirkin remarks:

Plato’s Laws—which Jaeger considered a major source on Hecataeus’s foundation story—recommended twelve tribes as the ideal number. Twelve-tribe alliances were a common feature in Greek tradition.

Contra the apologists of yore who thought Plato plagiarized Moses, Gmirkin theorizes that the creators of the Mosaic law had before them a copy of Plato’s Laws, at Alexandria during the third century BCE, when they drafted the Pentateuch as we know it.

While the Bible’s composition certainly dates to a later period, the Iron Age hill settlements who emerged as Israelites apparently already had a legal code of some sort, and we may surmise that Jewish priests and scribes accessed the libraries of Ashurbanipal and Babylon during the seventh and sixth centuries BCE. These facts do not preclude continuously reworking of oral traditions and texts for centuries until they took the shape in the Pentateuch, possibly influenced by Plato.

MEXICO’S TEZCATLIPOCA

His name is compounded of Tezcatepec, the name of a mountain (upon which he is said to have manifested himself to man) tlil, dark, and poca, smoke.

From the Codex Vaticanus;

Tezcatlipoca was one of their most potent deities; they say he once appeared on the top of a mountain. They paid him great reverence and adoration, and addressed him, in their prayers, as “Lord, whose servant we are.” No man ever saw his face, for he appeared only “as a shade.” Indeed, the Mexican idea of the godhead was similar to that of the Jews. Like Jehovah, Tezcatlipoca dwelt in the “midst of thick darkness.” When he descended upon the mount of Tezcatepec, darkness overshadowed the earth, while fire and water, in mingled streams, flowed from beneath his feet, from its summit.

CONCLUSION

Almost all nations of antiquity have legends of their holy men ascending a mountain to ask counsel of the gods, such places being invested with peculiar sanctity, and deemed nearer to the deities than other portions of the earth.

All peoples who had issued from a life of barbarism and acquired regular political institutions, more or less elaborate laws, and established worship, and maxims of morality, attributed all this—their birth as a nation, so to speak—to one or more great men, all of whom, without exception, were supposed to have received their knowledge from some deity.

“Whence did Zoroaster, the prophet of the Persians, derive his religion? According to the beliefs of his followers, and the doctrines of their sacred writings, it was from Ahuramazda, the God of light. Why did the Egyptians represent the god Thoth with a writing tablet and a pencil in his hand, and honor him especially as the god of the priests? Because he was ‘the Lord of the divine Word,’ the foundation of all wisdom, from whose inspiration the priests, who were the scholars, the lawyers, and the religious teachers of the people, derived all their wisdom. Was not Minos, the law-giver of the Cretans, the friend of Zeus, the highest of the gods? Nay, was he not even his son, and did he not ascend to the sacred cave on Mount Dicte to bring down the laws which his god had placed there for him? From whom did the Spartan law-giver, Lycurgus, himself say that he had obtained his laws? From no other than the god Apollo. The Roman legend, too, in honoring Numa Pompilius as the people’s instructor, at the same time ascribed all his wisdom to his intercourse with the nymph Egeria. It was the same elsewhere; and to make one more example,—this from later times— Mohammed not only believed himself to have been called immediately by God to be the prophet of the Arabs, but declared that he had received every page of the Koran from the hand of the angel Gabriel.”